[转]实际项目中如何使用Git做分支管理 (A successful Git branching model)

来自 https://nvie.com/posts/a-successful-git-branching-model/

In this post I present the development model that I’ve introduced for some of my projects (both at work and private) about a year ago, and which has turned out to be very successful. I’ve been meaning to write about it for a while now, but I’ve never really found the time to do so thoroughly, until now. I won’t talk about any of the projects’ details, merely about the branching strategy and release management.

Why git?

For a thorough discussion on the pros and cons of Git compared to centralized source code control systems, see the web. There are plenty of flame wars going on there. As a developer, I prefer Git above all other tools around today. Git really changed the way developers think of merging and branching. From the classic CVS/Subversion world I came from, merging/branching has always been considered a bit scary (“beware of merge conflicts, they bite you!”) and something you only do every once in a while.

But with Git, these actions are extremely cheap and simple, and they are considered one of the core parts of your daily workflow, really. For example, in CVS/Subversion books, branching and merging is first discussed in the later chapters (for advanced users), while in every Git book, it’s already covered in chapter 3 (basics).

As a consequence of its simplicity and repetitive nature, branching and merging are no longer something to be afraid of. Version control tools are supposed to assist in branching/merging more than anything else.

Enough about the tools, let’s head onto the development model. The model that I’m going to present here is essentially no more than a set of procedures that every team member has to follow in order to come to a managed software development process.

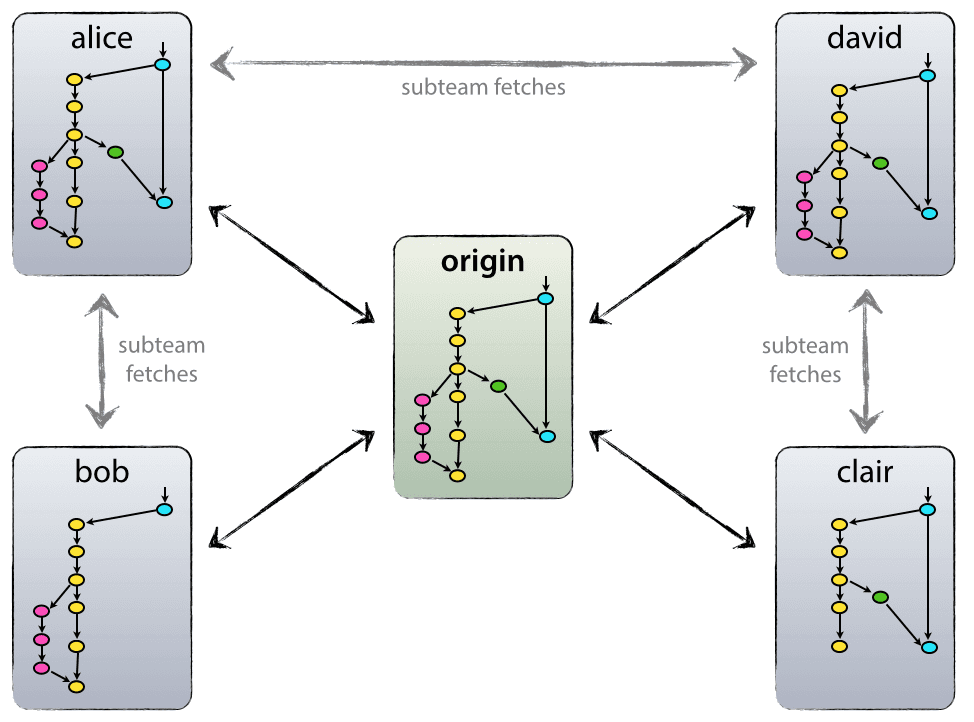

Decentralized but centralized

The repository setup that we use and that works well with this branching model, is that with a central “truth” repo. Note that this repo is only considered to be the central one (since Git is a DVCS, there is no such thing as a central repo at a technical level). We will refer to this repo as origin, since this name is familiar to all Git users.

Each developer pulls and pushes to origin. But besides the centralized push-pull relationships, each developer may also pull changes from other peers to form sub teams. For example, this might be useful to work together with two or more developers on a big new feature, before pushing the work in progress to origin prematurely. In the figure above, there are subteams of Alice and Bob, Alice and David, and Clair and David.

Technically, this means nothing more than that Alice has defined a Git remote, named bob, pointing to Bob’s repository, and vice versa.

The main branches

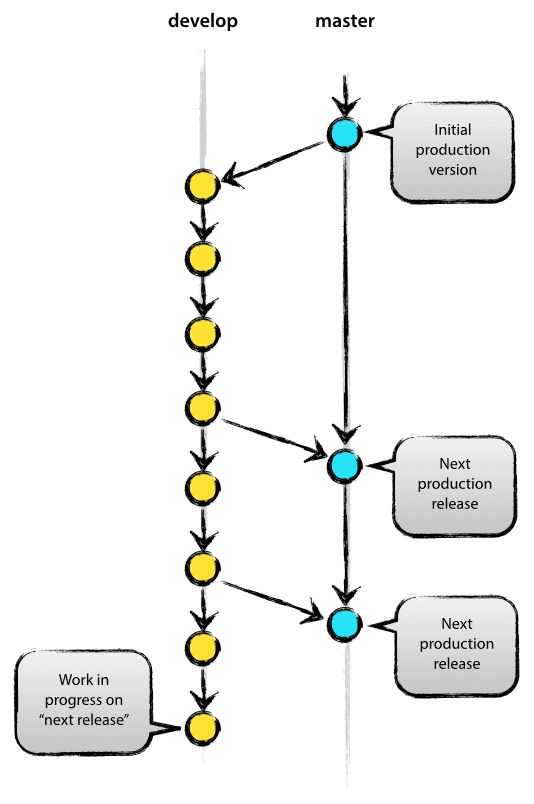

At the core, the development model is greatly inspired by existing models out there. The central repo holds two main branches with an infinite lifetime:

masterdevelop

The master branch at origin should be familiar to every Git user. Parallel to the master branch, another branch exists called develop.

We consider origin/master to be the main branch where the source code of HEAD always reflects a production-ready state.

We consider origin/develop to be the main branch where the source code of HEAD always reflects a state with the latest delivered development changes for the next release. Some would call this the “integration branch”. This is where any automatic nightly builds are built from.

When the source code in the develop branch reaches a stable point and is ready to be released, all of the changes should be merged back into master somehow and then tagged with a release number. How this is done in detail will be discussed further on.

Therefore, each time when changes are merged back into master, this is a new production release by definition. We tend to be very strict at this, so that theoretically, we could use a Git hook script to automatically build and roll-out our software to our production servers everytime there was a commit on master.

Supporting branches

Next to the main branches master and develop, our development model uses a variety of supporting branches to aid parallel development between team members, ease tracking of features, prepare for production releases and to assist in quickly fixing live production problems. Unlike the main branches, these branches always have a limited life time, since they will be removed eventually.

The different types of branches we may use are:

- Feature branches

- Release branches

- Hotfix branches

Each of these branches have a specific purpose and are bound to strict rules as to which branches may be their originating branch and which branches must be their merge targets. We will walk through them in a minute.

By no means are these branches “special” from a technical perspective. The branch types are categorized by how we use them. They are of course plain old Git branches.

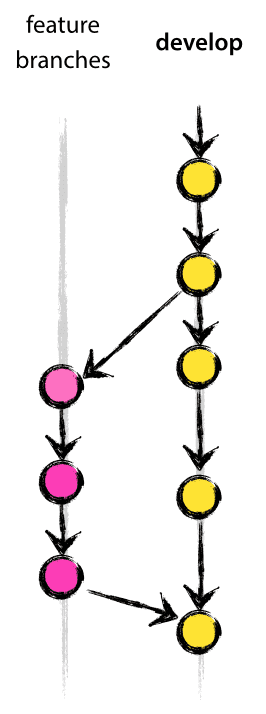

Feature branches

- May branch off from:

develop- Must merge back into:

develop- Branch naming convention:

- anything except

master,develop,release-*, orhotfix-*

Feature branches (or sometimes called topic branches) are used to develop new features for the upcoming or a distant future release. When starting development of a feature, the target release in which this feature will be incorporated may well be unknown at that point. The essence of a feature branch is that it exists as long as the feature is in development, but will eventually be merged back into develop (to definitely add the new feature to the upcoming release) or discarded (in case of a disappointing experiment).

Feature branches typically exist in developer repos only, not in origin.

Creating a feature branch

When starting work on a new feature, branch off from the develop branch.

$ git checkout -b myfeature develop

Switched to a new branch "myfeature"

Incorporating a finished feature on develop

Finished features may be merged into the develop branch to definitely add them to the upcoming release:

$ git checkout develop

Switched to branch 'develop'

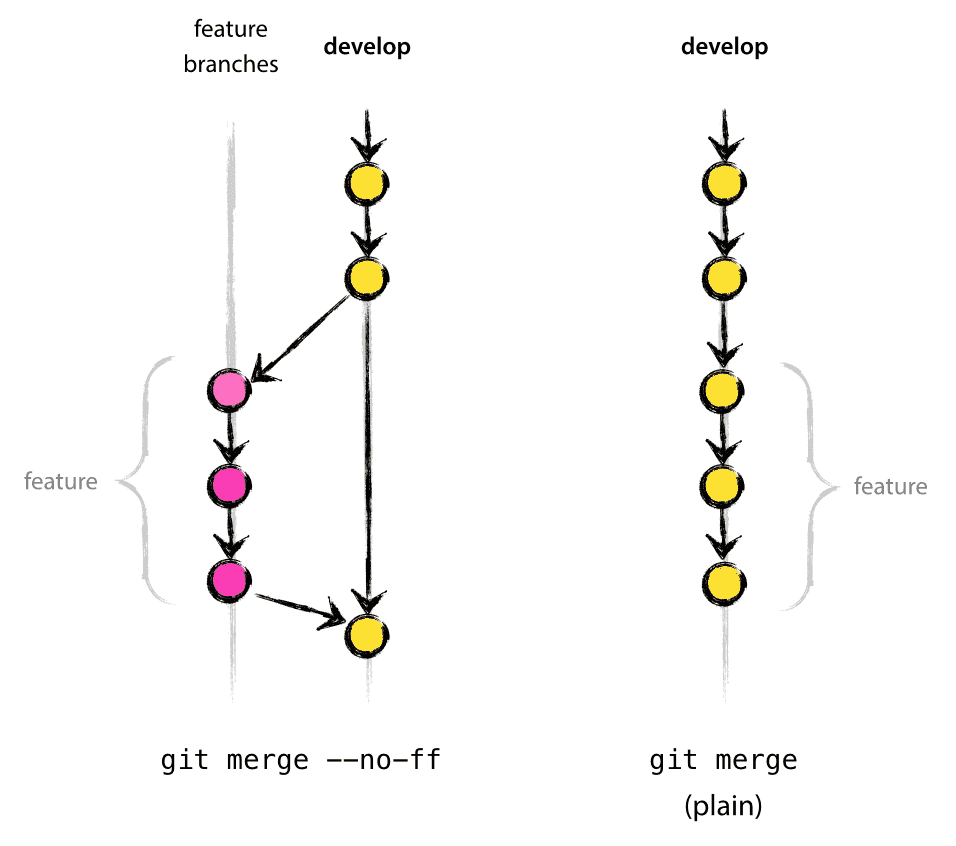

$ git merge --no-ff myfeature

Updating ea1b82a..05e9557

(Summary of changes)

$ git branch -d myfeature

Deleted branch myfeature (was 05e9557).

$ git push origin develop

The --no-ff flag causes the merge to always create a new commit object, even if the merge could be performed with a fast-forward. This avoids losing information about the historical existence of a feature branch and groups together all commits that together added the feature. Compare:

In the latter case, it is impossible to see from the Git history which of the commit objects together have implemented a feature—you would have to manually read all the log messages. Reverting a whole feature (i.e. a group of commits), is a true headache in the latter situation, whereas it is easily done if the --no-ff flag was used.

Yes, it will create a few more (empty) commit objects, but the gain is much bigger than the cost.

Release branches

- May branch off from:

develop- Must merge back into:

developandmaster- Branch naming convention:

release-*

Release branches support preparation of a new production release. They allow for last-minute dotting of i’s and crossing t’s. Furthermore, they allow for minor bug fixes and preparing meta-data for a release (version number, build dates, etc.). By doing all of this work on a release branch, the develop branch is cleared to receive features for the next big release.

The key moment to branch off a new release branch from develop is when develop (almost) reflects the desired state of the new release. At least all features that are targeted for the release-to-be-built must be merged in to develop at this point in time. All features targeted at future releases may not—they must wait until after the release branch is branched off.

It is exactly at the start of a release branch that the upcoming release gets assigned a version number—not any earlier. Up until that moment, the develop branch reflected changes for the “next release”, but it is unclear whether that “next release” will eventually become 0.3 or 1.0, until the release branch is started. That decision is made on the start of the release branch and is carried out by the project’s rules on version number bumping.

Creating a release branch

Release branches are created from the develop branch. For example, say version 1.1.5 is the current production release and we have a big release coming up. The state of develop is ready for the “next release” and we have decided that this will become version 1.2 (rather than 1.1.6 or 2.0). So we branch off and give the release branch a name reflecting the new version number:

$ git checkout -b release-1.2 develop

Switched to a new branch "release-1.2"

$ ./bump-version.sh 1.2

Files modified successfully, version bumped to 1.2.

$ git commit -a -m "Bumped version number to 1.2"

[release-1.2 74d9424] Bumped version number to 1.2

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

After creating a new branch and switching to it, we bump the version number. Here, bump-version.sh is a fictional shell script that changes some files in the working copy to reflect the new version. (This can of course be a manual change—the point being that some files change.) Then, the bumped version number is committed.

This new branch may exist there for a while, until the release may be rolled out definitely. During that time, bug fixes may be applied in this branch (rather than on the develop branch). Adding large new features here is strictly prohibited. They must be merged into develop, and therefore, wait for the next big release.

Finishing a release branch

When the state of the release branch is ready to become a real release, some actions need to be carried out. First, the release branch is merged into master (since every commit on master is a new release by definition, remember). Next, that commit on master must be tagged for easy future reference to this historical version. Finally, the changes made on the release branch need to be merged back into develop, so that future releases also contain these bug fixes.

The first two steps in Git:

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git merge --no-ff release-1.2

Merge made by recursive.

(Summary of changes)

$ git tag -a 1.2

The release is now done, and tagged for future reference.

Edit: You might as well want to use the

-sor-u <key>flags to sign your tag cryptographically.

To keep the changes made in the release branch, we need to merge those back into develop, though. In Git:

$ git checkout develop

Switched to branch 'develop'

$ git merge --no-ff release-1.2

Merge made by recursive.

(Summary of changes)

This step may well lead to a merge conflict (probably even, since we have changed the version number). If so, fix it and commit.

Now we are really done and the release branch may be removed, since we don’t need it anymore:

$ git branch -d release-1.2

Deleted branch release-1.2 (was ff452fe).

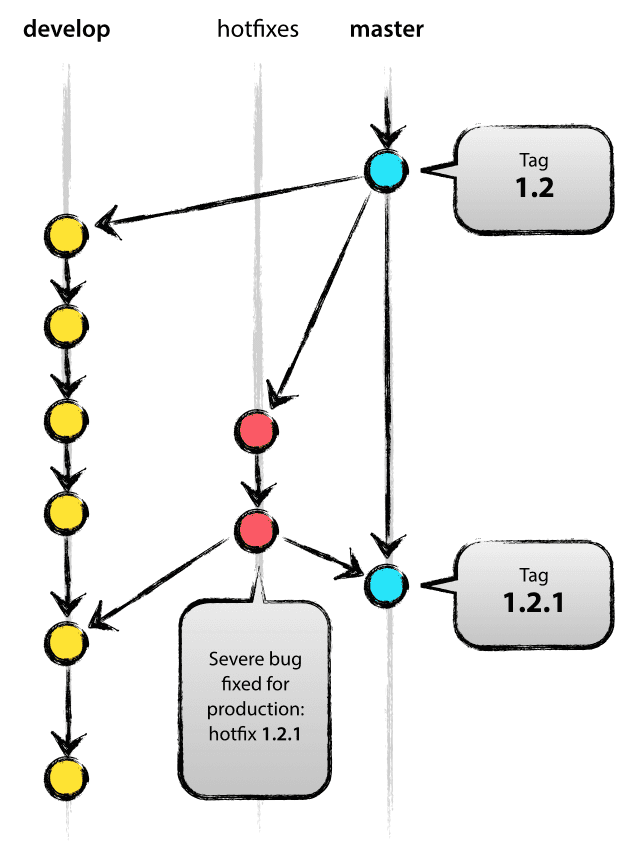

Hotfix branches

- May branch off from:

master- Must merge back into:

developandmaster- Branch naming convention:

hotfix-*

Hotfix branches are very much like release branches in that they are also meant to prepare for a new production release, albeit unplanned. They arise from the necessity to act immediately upon an undesired state of a live production version. When a critical bug in a production version must be resolved immediately, a hotfix branch may be branched off from the corresponding tag on the master branch that marks the production version.

The essence is that work of team members (on the develop branch) can continue, while another person is preparing a quick production fix.

Creating the hotfix branch

Hotfix branches are created from the master branch. For example, say version 1.2 is the current production release running live and causing troubles due to a severe bug. But changes on develop are yet unstable. We may then branch off a hotfix branch and start fixing the problem:

$ git checkout -b hotfix-1.2.1 master

Switched to a new branch "hotfix-1.2.1"

$ ./bump-version.sh 1.2.1

Files modified successfully, version bumped to 1.2.1.

$ git commit -a -m "Bumped version number to 1.2.1"

[hotfix-1.2.1 41e61bb] Bumped version number to 1.2.1

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 1 deletions(-)

Don’t forget to bump the version number after branching off!

Then, fix the bug and commit the fix in one or more separate commits.

$ git commit -m "Fixed severe production problem"

[hotfix-1.2.1 abbe5d6] Fixed severe production problem

5 files changed, 32 insertions(+), 17 deletions(-)

Finishing a hotfix branch

When finished, the bugfix needs to be merged back into master, but also needs to be merged back into develop, in order to safeguard that the bugfix is included in the next release as well. This is completely similar to how release branches are finished.

First, update master and tag the release.

$ git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

$ git merge --no-ff hotfix-1.2.1

Merge made by recursive.

(Summary of changes)

$ git tag -a 1.2.1

Edit: You might as well want to use the

-sor-u <key>flags to sign your tag cryptographically.

Next, include the bugfix in develop, too:

$ git checkout develop

Switched to branch 'develop'

$ git merge --no-ff hotfix-1.2.1

Merge made by recursive.

(Summary of changes)

The one exception to the rule here is that, when a release branch currently exists, the hotfix changes need to be merged into that release branch, instead of develop. Back-merging the bugfix into the release branch will eventually result in the bugfix being merged into develop too, when the release branch is finished. (If work in develop immediately requires this bugfix and cannot wait for the release branch to be finished, you may safely merge the bugfix into develop now already as well.)

Finally, remove the temporary branch:

$ git branch -d hotfix-1.2.1

Deleted branch hotfix-1.2.1 (was abbe5d6).

Summary

While there is nothing really shocking new to this branching model, the “big picture” figure that this post began with has turned out to be tremendously useful in our projects. It forms an elegant mental model that is easy to comprehend and allows team members to develop a shared understanding of the branching and releasing processes.

A high-quality PDF version of the figure is provided here. Go ahead and hang it on the wall for quick reference at any time.

Update: And for anyone who requested it: here’s the gitflow-model.src.key of the main diagram image (Apple Keynote).

[转]实际项目中如何使用Git做分支管理 (A successful Git branching model)的更多相关文章

- git的介绍、git的功能特性、git工作流程、git 过滤文件、git多分支管理、远程仓库、把路飞项目传到远程仓库(非空的)、ssh链接远程仓库,协同开发

Git(读音为/gɪt/)是一个开源的分布式版本控制系统,可以有效.高速地处理从很小到非常大的项目版本管理. [1] 也是Linus Torvalds为了帮助管理Linux内核开发而开发的一个开放源码 ...

- Git的分支管理

0.引言 本文参考最后的几篇文章,将git的分支管理整理如下.学习git的分支管理将可以版本进行灵活有效的控制. 1.如何建立与合并分支 1.1分支的新建与合并指令 新建分支 newBranch,并进 ...

- Git Flow 分支管理简述

概述 Git 是什么 Git 是一个开源的分布式版本控制系统,用于敏捷高效地处理任何或小或大的项目. Git 是 Linus Torvalds 为了帮助管理 Linux 内核开发而开发的一个开放源码的 ...

- 你真的了解git的分支管理跟其他概念吗?

现在前端要学的只是太多了,你是不是有时会有这个想法,如果我有两个大脑.一个学Vue,一个学React,然后到最后把两个大脑学的知识再合并在一起,这样就能省时间了. 哈哈,这个好像不能实现.现实点吧!年 ...

- Pull Request的过程、基于git做的协同开发、git常见的一些命令、git实现代码的review、git实现版本的管理、gitlab、GitHub上为开源项目贡献代码

前言: Pull Request的流程 1.fork 首先是找到自己想要pull request的项目, 然后点击fork按钮,此时就会在你的仓库中多出来一个仓库,格式是:自己的账户名/想要pull ...

- 项目中处理android 6.0权限管理问题

android 6.0对于权限管理比较收紧,因此在适配android 6.0的时候就很有必要考虑一些权限管理的问题. 如果你没适配6.0的设备并且权限没给的话,就会出现类似如下的问题: java.la ...

- git(二) 分支管理

概念 分支就是科幻电影里面的平行宇宙,当你正在电脑前努力学习Git的时候,另一个你正在另一个平行宇宙里努力学习SVN. 如果两个平行宇宙互不干扰,那对现在的你也没啥影响.不过,在某个时间点,两个平行宇 ...

- 139.00.005 Git学习-分支管理

@(139 - Environment Settings | 环境配置) 一.Why? 分支在实际中有什么用呢?假设你准备开发一个新功能,但是需要两周才能完成,第一周你写了50%的代码,如果立刻提交, ...

- git的使用学习(五)git的分支管理

分支管理 分支就是科幻电影里面的平行宇宙,当你正在电脑前努力学习Git的时候,另一个你正在另一个平行宇宙里努力学习SVN. 如果两个平行宇宙互不干扰,那对现在的你也没啥影响.不过,在某个时间点,两个平 ...

随机推荐

- sigmoid function的直观解释

Sigmoid function也叫Logistic function, 在logistic regression中扮演将回归估计值h(x)从 [-inf, inf]映射到[0,1]的角色. 公式为: ...

- BCNF/3NF 数据库设计范式简介

数据库设计有1NF.2NF.3NF.BCNF.4NF.5NF.从左往右,越后面的数据库设计范式冗余度越低. 满足后一个设计范式也必定满足前一个设计范式. 1NF只要求每个属性是不可再分的,基本每个数据 ...

- 如何手写实现简易的Dubbo[z]

[z]https://juejin.im/post/5ccf8dec6fb9a0321c45ebb5 前言 结束了集群容错和服务发布原理这两个小专题之后,有朋友问我服务引用什么时候开始,本篇为服务引用 ...

- oracle 四舍五入 取得的数值

SELECT ROUND( number, [ decimal_places ] ) FROM DUAL 说明: number : 将要处理的数值 decimal_places : 四舍五入,小数取几 ...

- jeecms v9图标不显示问题

- CentOS 升级 openSSH+ sh脚本自动运维

升级前后对比 openSSH作为linux远程连接工具,容易受到攻击,必须更新版本来解决,低版本有如下等漏洞: OpenSSH 远程代码执行漏洞(CVE-2016-10009) OpenSSH au ...

- java并发编程 线程基础

java并发编程 线程基础 1. java中的多线程 java是天生多线程的,可以通过启动一个main方法,查看main方法启动的同时有多少线程同时启动 public class OnlyMain { ...

- python 并发编程 基于gevent模块实现并发的套接字通信

之前线程池是通过操作系统切换线程,现在是程序自己控制,比操作系统切换效率要高 服务端 from gevent import monkey;monkey.patch_all() import geven ...

- Android 子线程无法刷新UI界面

问题:在Android开发中,子线程无法直接更改UI界面视图的刷新 这个时候 Handler 起到了至关重要的作用. 简单来说 , Handler就是用来传递消息的. Handler可以当成子线程与主 ...

- vue-loader介绍和单页组件介绍

$ \es6\sing-file> npm install vue-loader@14.1.1 -D vue-template-compiler@2.5.17 -D npm install v ...